My book project Addictive Forms revises a well-established narrative in nineteenth-century studies: that substance use gained unprecedented popularity in the nineteenth century, due to Britain’s worldwide advocacy and enforcement of psychoactive resources’ mass production and free trade; and that addiction was often politicized in this context, readily associated with “abnormal,” marginalized people marked by race, gender, class, health status, or other factors. Countering this narrative’s focus on individuals’ susceptibility to imperial power, Addictive Forms unveils a different perspective. It argues that addiction didn’t solely serve as imperial expansion’s consequence or tool acting on individual bodies, but rather as a method of imagining the structure of empire. I elaborate this argument by telling a story about how medical theories relevant to opium—a substance that caused and named the two Anglo-Chinese Opium Wars (1839–42 and 1856–60)—shaped nineteenth-century thoughts about empire in the context of Britain’s clash with the declining Chinese empire. The story shows that addiction-related medical models located in nineteenth-century literature an isomorphism between individual and imperial scales: authors adopted physiological forms from the various ways in which opium-using bodies react to stimulation to conceptualize and critique a new imperial structure that emphasized connectivity as opposed to isolation and self-reliance.

My argument adopts Caroline Levine’s concept of “forms.” In Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network, Levine demonstrates how “affordance” as an idea from design theory can reveal “both the specificity and the generality of forms” and unpack their possibilities and potentialities. Forms are “abstract organizing principles,” and therefore are “iterable” and “portable” and can “mov[e] back and forth across aesthetic and social materials.” As a form crosses contexts, it creates unpredictable effects, exposes a single pattern’s various potentials, and bridges the gap between incompatible scales. Though my object of study is primarily literary texts, the forms that underpin my analyses are abstract patterns provided by influential medical theories in the nineteenth century. I call these patterns “addictive forms,” not only because they are drawn from medical writings relevant to substance use and addiction, but also because they move across physiological models and political structures, in which we often find an “addictive” empire desiring or resisting stimulation from the world.

Addictive Forms is built on the premise that the history of imperial expansion both promoted and was facilitated by individual substance use and addiction. Starting from this premise, Addictive Forms goes beyond addiction’s negative implications such as fallenness and enslavement to explore the scientific mindset behind the opium-induced “technologies” of the body. By doing this, it considers the connection between addiction and empire from a new angle—how medical studies of these technologies provided models for the articulation of imperial violence. In each chapter I analyze literary works to address one conceptual category that structured the shared addictive form of opium’s effects on the body in medical theories and the stimulable, globalized empire in political thought. These categories include vigorousness, intoxication, inflation, physiognomy, olfaction, and addiction treatment, and each of them depends on archival research on specific medical theories and political thoughts. I conducted archival research for Addictive Forms at sixteen libraries in the US, the UK, China, France, and Singapore from 2016 to 2024. Among all these collections, the development of the project has significantly benefited from my visits to the Wellcome Library for the History and Understanding of Medicine and Yale University’s Medical History Library, Center for British Art, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, and Divinity Library.

At Yale, I explored theories about intoxication and addiction treatment by examining Presbyterian Church of England’s foreign missions archives, Asa P. Meylert’s notes on the opium habit, naval documents, logbooks, and diaries, and a number of illustrations relevant to the opium trade and opium wars. They offer significant perspectives on the pathologization of addiction in the late nineteenth century—especially medical missionaries’ important role in shaping the idea of addiction treatment—and the commonality between medical studies of intoxication, which affects psychical time, and representations of the sense of time in sea travel. At Wellcome, collections such as reports of medical missionary society and missionary hospitals allowed me to further trace the emergence of addiction treatment. In medical missionaries’ medical practices and categorization of disease, the category opium use appeared in the late nineteenth century alongside a variety of other medical cases, from “rheumatic affections,” “paralysis,” to “tumours” and “dog bites.” In addiction to these collections, medical writings and illustrations on physiognomy I consulted at Wellcome contributed to my accounts of physiognomic studies of race and illness by people such as the Swiss physiognomist Johann Lavater and the Scottish physician Alexander Morison, which helped shape my argument about physiognomic taxonomy’s methodological affinities with imperial knowledge-making in nineteenth-century literature. I also found papers and lectures on olfaction and opium smelling at Wellcome. Describing the sense of smell as vibration or the “immigration” of matter, the medical model opens up the possibility of envisioning the macroscale mechanisms of influence, interdependence, and immigration in the global context.

My time at Yale University and Wellcome Collections offered critical insights into nineteenth-century medical theories on addiction and substance use. With the support of the Consortium for History of Science, Technology and Medicine Research Fellowship, I was able to explore various forms of addiction and find that they informed thoughts about imperial structures in ways more surprising than I expected. Thanks to the archival resources, the interdisciplinary project therefore also reveals a history of how the connection between addiction and the abnormal still came into being while the nineteenth century presented alternative models. I aim to persuade the reader that imperial violence’s intersection with medicine was embodied not only in its pathologization or racialization of enemies and outliers but also in stimulation patterns such as invigorating, progressive, and expansive models that liberate the self. In addition, the mechanisms of opium use’s connection with pathology provided astoundingly diverse forms—such as repetition of physiognomies, influence as migration of matter, and treatment and recovery—to dissect and critique imperial supremacy in productive ways.

|

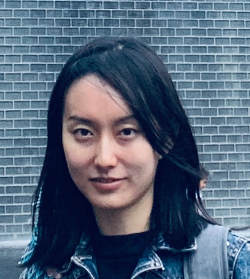

Menglu Gao is Assistant Professor of Victorian Literature in the Department of English and Literary Arts at the University of Denver. She is a 2019–2020 Consortium Research Fellow.

Menglu Gao is Assistant Professor of Victorian Literature in the Department of English and Literary Arts at the University of Denver. She is a 2019–2020 Consortium Research Fellow.