Michael Sappol is a 2017-2018 Research Fellow and is a Research Fellow at Uppsala University.

Michael Sappol is a 2017-2018 Research Fellow and is a Research Fellow at Uppsala University.

Over the past 40 years scholars have intensively studied the history of medical photography — photographic clinics, medical portraiture, forensic medicine, photomicrography, x-radiography, and so on. But oddly, missing from that list is the field that for centuries stood at the heart of the medical curriculum, and whose images had a privileged status in the hierarchy of medical publication: anatomy.

Photography, with its powerful “reality effect,” was an emblematic technology of science and modernity. Physicians and surgeons eagerly adopted it, showed an ardent desire to photograph pathological conditions, microscopic views, laboratory experiments, surgical techniques, etc. The medical photograph had rhetorical advantages, persuaded viewers that it was a close proxy for unmediated reality. The photograph, it seemed, could fix on paper or glass a view of what would be visible if the object could be witnessed with the unbiased naked eye. And that was potentially useful in mounting a critique of anatomical illlustrationism and aesthetics as unscientific.

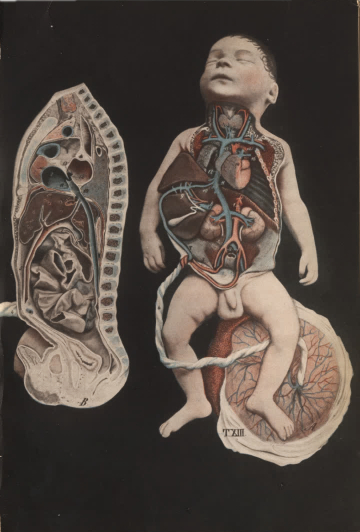

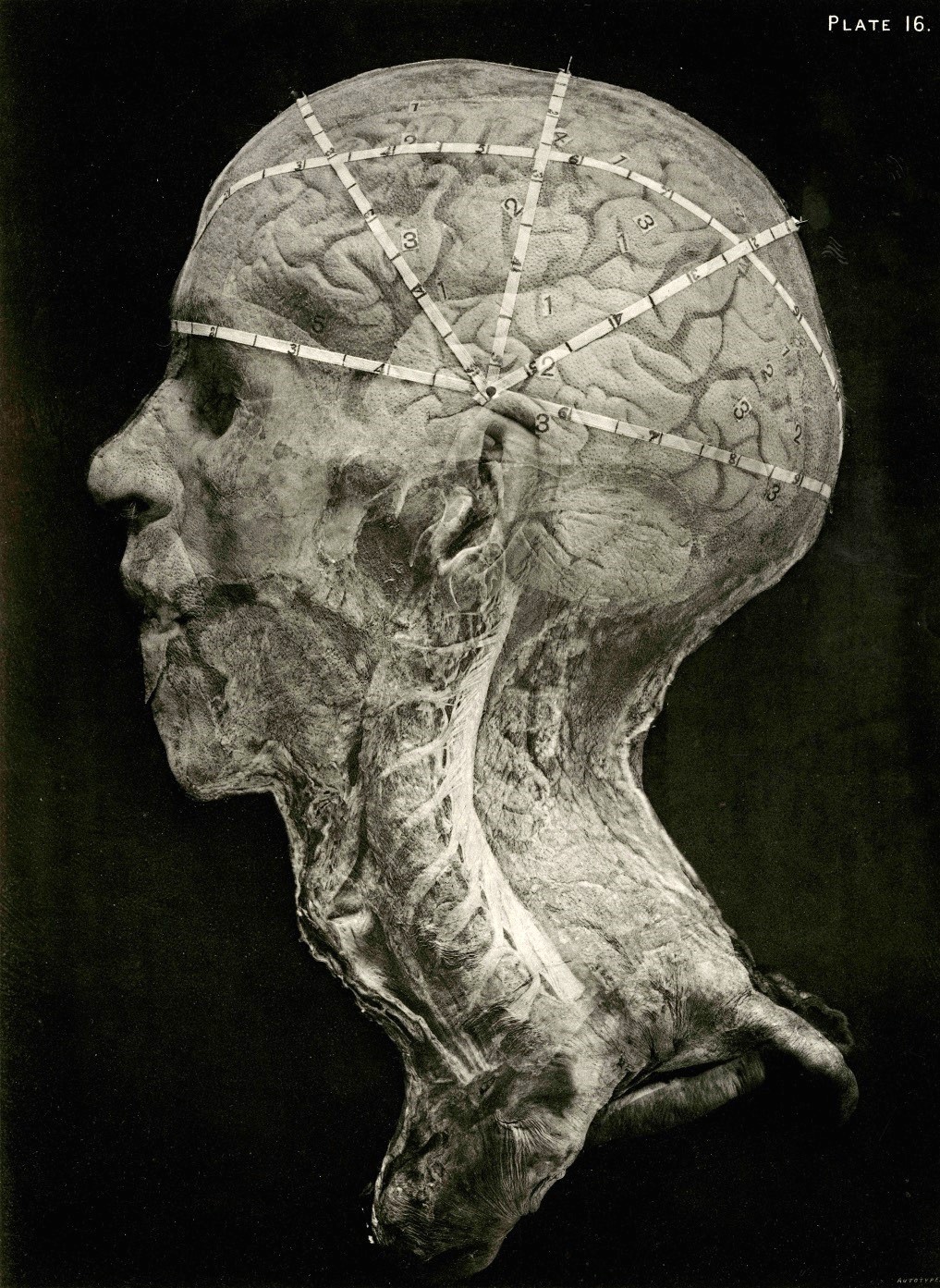

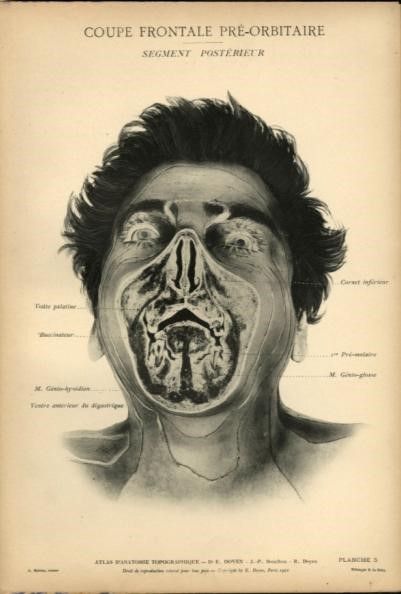

But anatomy only fitfully embraced photography. In the 1860s and succeeding decades, when Nicolaus Rüdinger, Eugène-Louis Doyen and other anatomists finally took to it, they took liberties. They cut, sliced, posed, and lit their cadavers and body parts in novel and idiosyncratic ways. Their photographs were then retouched, silhouetted or colored, and outfitted with a halo of captions. The artist’s pen and brush were as evident as the anatomist’s saw and scalpel — and both were subject to an aesthetic impulse.

But anatomy only fitfully embraced photography. In the 1860s and succeeding decades, when Nicolaus Rüdinger, Eugène-Louis Doyen and other anatomists finally took to it, they took liberties. They cut, sliced, posed, and lit their cadavers and body parts in novel and idiosyncratic ways. Their photographs were then retouched, silhouetted or colored, and outfitted with a halo of captions. The artist’s pen and brush were as evident as the anatomist’s saw and scalpel — and both were subject to an aesthetic impulse.

The resultant objects were eccentric, provocative photographic/nonphotographic hybrids. And part of the shock came from the photographic critique of beauty in anatomical illustration and a corresponding revaluation of ugliness. If the artist’s desire to beautify the image was a vector of falsification, and photographic uglinesss a signifier of the real, then the entire category of beauty was fraught. And this had a paradoxical result: the anatomical photograph stands as an anti-aesthetic object, but also works to revise and transform the criteria by which beauty is accounted for. There could be beauty in the truth of ugliness, and beauty in the artful photographic presentation of ugly reality (a paradox that was not confined to photographic images, but evident in the 16th-century works of Vesalius, there at the creation of the modern anatomical atlas).

Even so, photography—ubiquitous in every other medical subdiscipline—never became the dominant mode of anatomical illustration, never succeeded in displacing the medical illustrator. The field of anatomy was too committed to its tradition of artful drawing and artist-anatomist collaboration. But photography did have a vogue among ambitious young anatomists. Between 1861 and 1950, that modernizing vanguard created and published thousands of photographs in Germany, France, the USA, Canada, England, Scotland, Argentina, Ireland, Sweden and elsewhere. Aided and abetted by continual improvements in the technologies of photograph and print reproduction, photographic anatomy became a global movement.

Even so, photography—ubiquitous in every other medical subdiscipline—never became the dominant mode of anatomical illustration, never succeeded in displacing the medical illustrator. The field of anatomy was too committed to its tradition of artful drawing and artist-anatomist collaboration. But photography did have a vogue among ambitious young anatomists. Between 1861 and 1950, that modernizing vanguard created and published thousands of photographs in Germany, France, the USA, Canada, England, Scotland, Argentina, Ireland, Sweden and elsewhere. Aided and abetted by continual improvements in the technologies of photograph and print reproduction, photographic anatomy became a global movement.

A movement which was entangled with topographical anatomy, medical museology and other efforts to modernize the field. But more than that: photography changed how anatomists did anatomy, and anatomy changed how anatomists did photography. There were new varieties of anatomy and new approaches to photographic anatomy: cross-sectional studies, regional studies, multipronged studies of parts, stereoscopic and composite studies, and so on.

My project, tentatively titled Anatomy’s Photography, aims to consider anatomical photographic practice in relation to the changing epistemological status, scientific claims, rhetorical power, aesthetics, and moral implications, of anatomical photography as were then debated — and as we debate them still.

My project, tentatively titled Anatomy’s Photography, aims to consider anatomical photographic practice in relation to the changing epistemological status, scientific claims, rhetorical power, aesthetics, and moral implications, of anatomical photography as were then debated — and as we debate them still.

It is a large investigation into an understudied field, and therefore somewhat exploratory. At this stage, I’m working on various aspects of anatomy and photography as they intersect, from the 1860s up until around 1950, a rich lode of photographic studies produced on three continents between 1860 and 1950. As I go, I collect digital images of the anatomists and photographers and their work, where such materials can be found.

And I’m collecting stories: about anatomists: at the margins and the center, improvising and performing photography to perform anatomy as a modern science, improvising and performing themselves as scientific moderns. Nikolaus Rüdinger, son of a poor farmer and trained as a barber-surgeon before attending the full course of medicine at Heidelberg, devised the first anatomical photographic study in the 1860s and produced several subsequent studies in collaboration with Bavarian court photographer Joseph Albert. Eugène-Louis Doyen, mostly known as a pioneer of the medical motion picture, also made an atlas of still photographs of provocatively posed anatomical subjects that scandalized the Parisian medical establishment in the early 20th-century. His contemporary, Eliseo Cantón, a modernizing conservative Argentinian politician-physician, made an astonishing life-size photographic obstetrical atlas out of the cross-sectioned bodies of pregnant women and babies who died in the Buenos Aires obstetrical clinic that he directed. Pedro Belou, George McClellan, Jules-Bernard Luys, Alec Fraser, John Shaw Billings, William Macewen, all important figures with many stories…

What all of them have in common is a how-to-get-modern story. In the middle and later decades of the 1800s, gross anatomy stood at a crossroads. While, for centuries, anatomy had stood at the heart of the medical curriculum and the forefront of medical science, other fields now increasingly occupied stage-center of the program to scientize medicine. Where students once clamored to dissect, they now clamored to work with microscopes and scientific instruments in the clinic and laboratory: pathology, microbiology, embryology, psychiatry and physiology became the exciting fields. For anatomy to be performatively modern and scientific, it had to find new methods, research agendas and technologies, and that meant, among other things, photography.

What all of them have in common is a how-to-get-modern story. In the middle and later decades of the 1800s, gross anatomy stood at a crossroads. While, for centuries, anatomy had stood at the heart of the medical curriculum and the forefront of medical science, other fields now increasingly occupied stage-center of the program to scientize medicine. Where students once clamored to dissect, they now clamored to work with microscopes and scientific instruments in the clinic and laboratory: pathology, microbiology, embryology, psychiatry and physiology became the exciting fields. For anatomy to be performatively modern and scientific, it had to find new methods, research agendas and technologies, and that meant, among other things, photography.

I am currently based in Stockholm and Uppsala in Sweden, a good location to explore European collections. But some of the great North American libraries also hold anatomical photograpic materials. Funded by the Consortium for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine, I was able to do research in the special collections of the New York Academy of Medicine (NYAM), the August Long Health Sciences Library and Butler Library of Columbia University, and the Cushing Historical Medical Library at Yale. On my trip I found works of photographic anatomy and other materials relating to Rüdinger, Doyen, Cantón and Belou. And, at NYAM and Yale, I got the opportunity to immersively view Belou’s stereographic images through a stereoscopic viewer, as they were meant to be seen. A rare treat.