Arnaud Zimmern is postdoctoral research fellow at the Navari Family Center for Digital Scholarship of the University of Notre Dame, where he designs virtual reality (VR) applications for research and teaching in the Humanities and facilitates graduate-level training in inclusive digital pedagogy. His research focuses on early modern medicine, science, and literature.

Drinking Gold: Why Shakespeare’s “Med’cine Potable” Is Not Like The Others

In 2020, when I was awarded a CHSTM short-term research fellowship, I was a doctoral candidate in English literature with a focus on bringing Shakespeare, Milton, and their contemporaries to bear on standing debates around the trajectory of medical progress in the 17th and 21st centuries. My dissertation uncovered early modern England’s culture of panaceas, or cure-alls, and highlighted a growing divide over a fundamental question: should medicine pursue the cure of all diseases, including aging and death, or accept certain limits and admit certain ills as incurable? As I wrote, the Covid pandemic raged, and even as vaccines seemed to approach, the same divide I observed in seventeenth-century Europe seemed to persist and widen in modern-day America: techno-optimism and resigned pragmatism squared off, as thought-leaders pitched divergent stories for the futures of medical innovation.

Out of that dissertation, with its focus on literature, its genres, its lineages, emerged a more conceptual and historical book project, which I am titling The Cure of All: Panaceas and the Narrative of Medical Progress, 1595-1700. It showcases how seventeenth-century playwrights, essayists, and poets together with alchemists, physicians, and natural philosophers gave shape to a fundamentally modern equivocation, an ambiguity over how best to condemn peddlers of panaceas while still holding out hope for everything that they promise? The book not only seeks to articulate how, against the run of play, great works of early modern literature established trendsetting critiques of medicine’s purported progress and paved the way for the likes of Shelley’s Frankenstein or Zola’s Docteur Pascal. It also articulates how medicine’s narrative of unrelenting progress emerged as a response to early modern narratives of medical regress, i.e. fears, anxieties, and occasionally valid warnings that our very efforts to cure all ills might be sending us backwards or leading us nowhere.

For the fellowship, I focused my research on better understanding the most popular, if most forgotten panacea of the early modern period: potable gold, or aurum potabile as medieval and early modern alchemists often spoke of it. Within the extant scholarship on alchemy’s lofty aspirations to universal health, potable gold has gotten its fair share of attention, not least for its proponents' odd claim that gold’s virtue of incorruptibility could be imbibed. This honeyed preparation was widely coveted, it inspired chemists late into the 17th century including Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton, and it sparked controversial debates in European royal courts between mainstream physicians, empirics, and the aristocrats who sponsored their research and development.

Yet on the early modern stage, potable gold was almost universally a laughing matter. In the dramas of the Elizabethan and Jacobean era, it was never a cure but almost always a euphemism for liquid cash, bribery, and social capital. Invariably, aurum potabile was invoked as an inside joke about what gold is really worth and what it can really do. Only occasionally was it staged as a quack medicine peddled to the overly-optimistic, as in Ben Jonson’s satirical play The Alchemist. And only once was it none of those things but merely, well, itself: a rare and wondrous panacea.

That one instance is William Shakespeare’s deathly serious historical drama Henry IV Part II, a dark play about Machiavellian politics and the disenchantment of divine-right monarchy. At the apex of its emotionally tense storyline between the dying patriarch Henry Bolingbroke and his disingenuous next-in-line Prince Hal, the younger man assures his father that he never coveted the crown; he only wishes he could replace it instead with “med’cine potable.” Holding the royal circlet like Hamlet holds Yorick’s skull, Hal performs for his two audiences (the king and us) a humble yet heroic dis-investiture, berating the crown for the cares it has imposed on the king’s body before returning it to its rightful bedridden owner:

thou best of gold art worst of gold.

Other, less fine in carat, is more precious,

Preserving life in med’cine potable;

But thou, most fine, most honored, most renowned,

Hast eat thy bearer up. (4.3.317-321)

To better understand why at this crucial juncture Shakespeare’s Prince Hal evokes a panacea that theater-goers were trained to deem ridiculous and implausible but that many (noble and plebeian alike) were prone to patronize and seek out, I struck out in summer 2022 to the Wellcome Collection in London.

With one of the deepest archives on alchemy the world around, the Wellcome Library provided me with an ideal venue in the midst of London’s summer heat to focus on the sweaty efforts that Shakespeare’s contemporaries invested in making gold drinkable. I wanted to fathom the appeal of potable gold, particularly for those who make the drug. If I were a panacea-maker, how would I come to believe in my own wares? That question lingers in the air for any scholar of Paracelsus or van Helmont, two of the premier panacea-peddlers and medical reformers of the Renaissance; but it is on the table also for scholars of modern restorative, regenerative, and anti-aging medical techniques in their pre-experimental stage: how does one find hope in a hunch or theory? Especially in the wake of Elizabeth Holmes’ trial over the Theranos bioethic fraud affair, I was primed, like many others, to wonder about the role of sincere belief in the issuance of therapeutic promises.

One manuscript recipe collection at the Wellcome yielded particularly rich insights. Attributed to an unknown R. Nelson, this bound volume written in two different hands contains at least seven recipes for potable gold, each considerably different. Catalogers at the Wellcome had noted the mixed use of Latin and English; I pointed out the additional use of French, which broadens the international ambit of the text and the possible identities of its composers. It will be the work of the next few months to transcribe those pages, but what is readily evident is that the compiler or compilers were registering competing dynamics between recipes for ostensibly the same drug. Somehow, potable gold recipes were not all created equal but all pretended to the same glorious effects. The implications of those differences are complex for those who believed in potable gold’s efficacy on theoretical grounds.

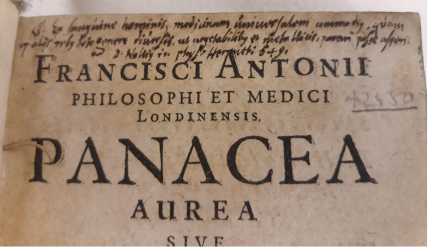

In a similar way, in the Library’s copy of Francis Anthony’s Panacea aurea (1618), arguably the most famous print book on potable gold in Jacobean England, an unknown seventeenth-century hand has left a revealing inscription on the title page. With help from William Schupbach, Research Development Specialist at the Wellcome, I learned that it reads “the panacea can more conveniently be prepared from human blood than from other things that are different in every way such as vegetable and metallic matter.” After stomaching the idea that the early moderns may have used human blood pharmaceutically, I was left to ponder the criteria with which panacea-makers were comparing and assessing the relative efficacy (or in this case, the relative convenience) of various recipes for the same potion. The inscription at the head of the title-page rings an almost casual note: its writer seems nonplussed by the feasibility of a panacea that (so Anthony claims) truly cures all diseases and seems convinced one might even do better. It is the source of that confidence I seek to better understand.

Francis Anthony, Panacea Aurea (Hamburg: Ex Bibliopolio Frobeniano, 1618), title page. Early European Books, Copyright © 2017 ProQuest LLC. Images reproduced by courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London. Held at the Wellcome Collection, Closed stores, EPB/A/335

The note reads: “Ex sanguine hominis, medicinam universalem commodius quam ex aliis rebus toto genere diversis ut vegetabilibus et metallicis, parari posse asserit D. Nollius in phys. Hermetis 649."

A translation, courtesy of William Schupbach: Mr Nollius [i.e. Henricus Nollius, or Heinrich Nolle] says [in his commentary on] the Physica of Hermes [Trismegistus], [page] 649, that the panacea can more conveniently be prepared from human blood than from other things that are different in every way such as vegetable and metallic matter."

The next steps in my work will involve sifting more methodically through R. Nelson’s recipe collection and other copies of Anthony’s printed works at other Consortium collections like the New York Academy of Medicine and Yale’s Beineke Library. Amongst the discrepancies between recipes for panaceas lie larger discrepancies between the theories and self-confidence of panacea-makers. Through them, I hope to obtain insights into the cultural narratives and hesitations surrounding medicine’s progress that so formidably shaped literar moments like Prince Hal’s monologue to the crown. As for future published work, these archival findings will become part of the broader book project on panaceas and progress and appear in a scholarly entry on panaceas solicited by Routledge Resources Online - The Renaissance World.

Needless to say, it has been invaluable to have the Consortium’s support, with its repeated encouragements not to give up on archival research in the wake of the pandemic but to return to primary materials for new insights. Without the examples of younger scholars in the Early Modern Science working group, I may not have gathered the gumption to take up this project again and forge ahead. For their kind words and outstanding efforts, an immense thank-you to Consortium staff.